Christopher Rufo vs. The New Yorker

Old tweets, new norms, and the 2014 tipping point

The writer Doreen St. Félix has struck gold twice. In 2017, at the age of 25, she secured a staff position at the ne plus ultra of literary prestige, The New Yorker. Then, this week, her profile rose again when she became the subject of a pile-on from conservative activist Christopher Rufo, who decided to punish her for an August 2 think piece about American Eagle’s supposedly racist ad campaign featuring the actress Sydney Sweeney. Rufo’s method of choice? That reliable standby: decades-old tweets.

Those tweets, oh-so-mid-2010s, went like this.

The offending article, very 2022 with a dash of Judith Butler circa 1990, went like this.

Rufo’s beef was that this wasn’t just a matter of bad tweets from long ago. St. Félix, a run-of-the-mill Twitter racist (aka an anti-racist racist) in her youth, had become a grown-up normal racist writing for the post-woke New Yorker. (As was noted last March in Compact, the magazine hasn’t published a single piece of fiction by a white man under 40 since 2020.) Under the pretense of anti-racism, The New Yorker had hired a racist. The hypocrisy! Rufo could not abide it, so he went on an outrage archaeology excursion and dug up a trove of incriminating receipts. Just a leisurely dog day afternoon in August.

St. Félix was born in 1992, which means she would have been around 22 years old and recently graduated from Brown University when she sent those tweets. She majored in creative nonfiction writing, and the degree served her well. In 2015 she published an essay in Pitchfork, The Prosperity Gospel of Rihanna, that was deemed a literary breakthrough. The Huffington Post included the essay on its “Most Important Writing From People Of Color” list in 2015, and Paper Magazine declared it “the best damn thing ever written [about] Rihanna.”

St. Félix was on the ascent. In 2016, while writing for MTV News and Lena Dunham’s publication Lenny Letter, she was included on Forbes’s “30 under 30” list as well as Brooklyn Magazine’s list “100 Most Influential People in Brooklyn Culture.” The next year, she got The New Yorker job, where she won a National Magazine Award for cultural criticism. In 2019 she was named television critic, the youngest person in the magazine’s history to hold that position.

The thing about The New Yorker is that the editing is so good that even the worst writers, if they manage to squeeze past the gates, are drill-sargeanted into higher-than-average readability.

If you’re waiting for me to wax apoplectic about what a bad writer St. Félix is, you’ll be waiting a while. The thing about The New Yorker is that the editing is so good that even the worst writers, if they manage to squeeze past the gates, are drill-sargeanted into higher-than-average readability. In an interview in November magazine, St. Felix credited her New Yorker editor as someone “who completely changed my life . . . the most intense relationship of my 20s.”

As weird and contorted as the Sweeney piece is, I’ve enjoyed some of St. Félix’s articles over the years, including this one gently mocking Democratic politicians wearing African kente stoles. And while “The Prosperity Gospel of Rihanna” reminds me of the kind of student work that, back when I taught in MFA programs, was engineered to fool classmates (and occasionally instructors) into seeing its incoherence as brilliance (“I’m blown away by my own confusion,” the brooding boy in the back will say), I’m not going to use this space to litigate its merits or lack thereof. If it’s not the best damn thing ever written about Rihanna, I have no doubt it’s at least in the top five; respect must be paid.

What I do want to address is Rufo’s apparent, if not explicitly stated, goal of shaming The New Yorker into firing, or at least publicly censuring, St. Félix over her tweets. Sorry, but it’s a fool’s errand. Rufo can flail and seethe all he likes, but if he thinks that New Yorker editor David Remnick is going to behold St. Félix’s tweets and be shocked—shocked—that one of his star cultural critics (one of Brooklyn culture’s most influential people, no less) could be capable of such crassness and fanaticism, he’s missing a crucial piece of the cultural picture.

That piece might as well be labeled “2014” and placed under glass in the Museum of Contemporary American Meltdown.

2014 was the last normal year of American cultural life.

Let’s talk about 2014. It was the last normal year of American cultural life. Yes, the world of the New York media commentariat was beginning to shift on its axis—the Black Lives Matter movement was changing norms about what could and could not be said about race—but it was still rotating in more or less the same direction.

I had a book come out that year—The Unspeakable, after which my podcast was named—and it was embraced by critics despite presenting some challenging and potentially unpopular ideas. It was also excerpted, at considerable length, in The New Yorker. Tumblr, the microblogging site that turned out to be a key incubator of the fandom, social justice writing, and queer self-discovery that would define the subsequent decade, was at peak popularity in 2014, but it hadn’t yet escaped containment into mainstream life.

Lena Dunham, a bona fide celebrity whose Tumblr vibe peacefully coexisted with her conventional artistic ambitions, was all over the place in 2014 thanks to the publication of her much-anticipated memoir, Not That Kind of Girl. I wrote a long profile of Dunham for the New York Times that fall, and my comparisons of her work to Woody Allen’s work were taken as a perfectly reasonable—and largely flattering—analogy.

A few years earlier, I had been profiled for a magazine alongside a fellow writer who was about ten years my junior and whose work was often compared to mine. The interviewer asked who we considered our “ideal readers.” Caught off guard, I said something like, “Uh, anyone who wants to read the book?” The other writer said, “Young women with Tumblr accounts.”

I didn’t know what Tumblr was then and I still didn’t quite know in 2014. I did know something was in the air. Sometime that year, the younger writer and I had dinner together (in Brooklyn, natch), and I tried to explain what I was noticing. The signal force was Roxane Gay, whose career-defining essay collection Bad Feminist had come out that summer. Gay’s star was rising fast, propelled by young progressive white women whose fandom, as I saw it, was less about Gay’s writing than about the opportunity she afforded them to feel less racist by virtue of that fandom. At the time, Gay was not yet the social justice superstar and Twitter bully she would later become. In November of 2014, she’d reviewed my book favorably for the New York Times.

Within a year, Gay would be the sort of person to avoid me at parties, lest she be accidentally photographed next to an actual bad feminist. Within five years, my dinner companion (who, incidentally, said she thought Gay would be a flash in the pan) would be publicly condemning my tragic crossing to the wrong side of history. But for the moment, it was still 2014. Obama was in the White House. Lena Dunham was the toast of the town. And Brown University types were ranting about whiteness from the relative obscurity of Twitter and on Tumblr. All fun and games.

And then came 2015. And, worse, 2016. I needn’t go on. (I’ve had plenty to say in the past, in case you missed it.)

St. Félix doesn’t work at The New Yorker in spite of such tweets. She works there because of them.

The Christopher Rufos of the world entertain fantasies that the David Remnicks of the world will learn of tweets like St. Félix’s, recoil in shame for insufficiently vetting their staff, and make the necessary firings, possibly relieving themselves of their own responsibilities in the process. But what Rufo and his acolytes do not understand is that St. Félix doesn’t work at The New Yorker in spite of such tweets. She works there because of them.

After 2014, the milieu in which every very young, aspiring cultural critic operated was the milieu of social justice opportunism. In this milieu, the baseline vernacular was profane, the central conceit was narcissism disguised as self-care, and punching was okay, even encouraged, as long as you were punching up to power.

“Whiteness must be abolished” was the “globalize the intifada” of its time.

Sentiments like “I hate white men. You are the worst,” while shocking and offensive to the un-Tumblred ear, were simply what was fashionable during the first Trump administration. “Whiteness must be abolished” was the “globalize the intifada” of its time. It was meant to signify style, not, you know . . . meaning. The only people making a big deal of it were out-of-touch oldsters with no understanding of intersectional power systems. Talk about cringe.

Fearing a descent into irrelevance, institutions like The New Yorker “met the moment” by grabbing onto flashy, underdeveloped young talent for dear life. And if that talent happened to emerge from the hothouse of Tumblr and its attendant baggage of sophomoric rants and bad tweets (not to mention hipster antisemitism), well, this could be overlooked in the name of historical right-side-ism.

There’s still consistently great writing at the magazine. But not many of the writers hired in the past decade at The New Yorker feel much like New Yorker writers. Is this the result of the rather blunt instrument the magazine took to its diversity initiatives in recent years? Is it because many established writers are on Substack now, where they can often make more money plus not have to contend with hyper-demanding editing and fact-checking? Or is it just the sad, boring fact that most readers lack the attention span for long-form narrative nonfiction? (Except on Substack, where they’re frequently happy to read 5,000 words as long as they feel they have a personal relationship with the writer.)

I would say the answer is yes to all three, but ultimately it doesn’t matter. It doesn’t matter because most of American culture—and certainly American politics—now operates on a does-not-matter basis. What Rufo fails to understand is that The New Yorker, too, does not matter nearly as much as it once did. Though in his latest effort, he’s made it matter more than it has in a long time. Maybe they should hire him.

Housekeeping

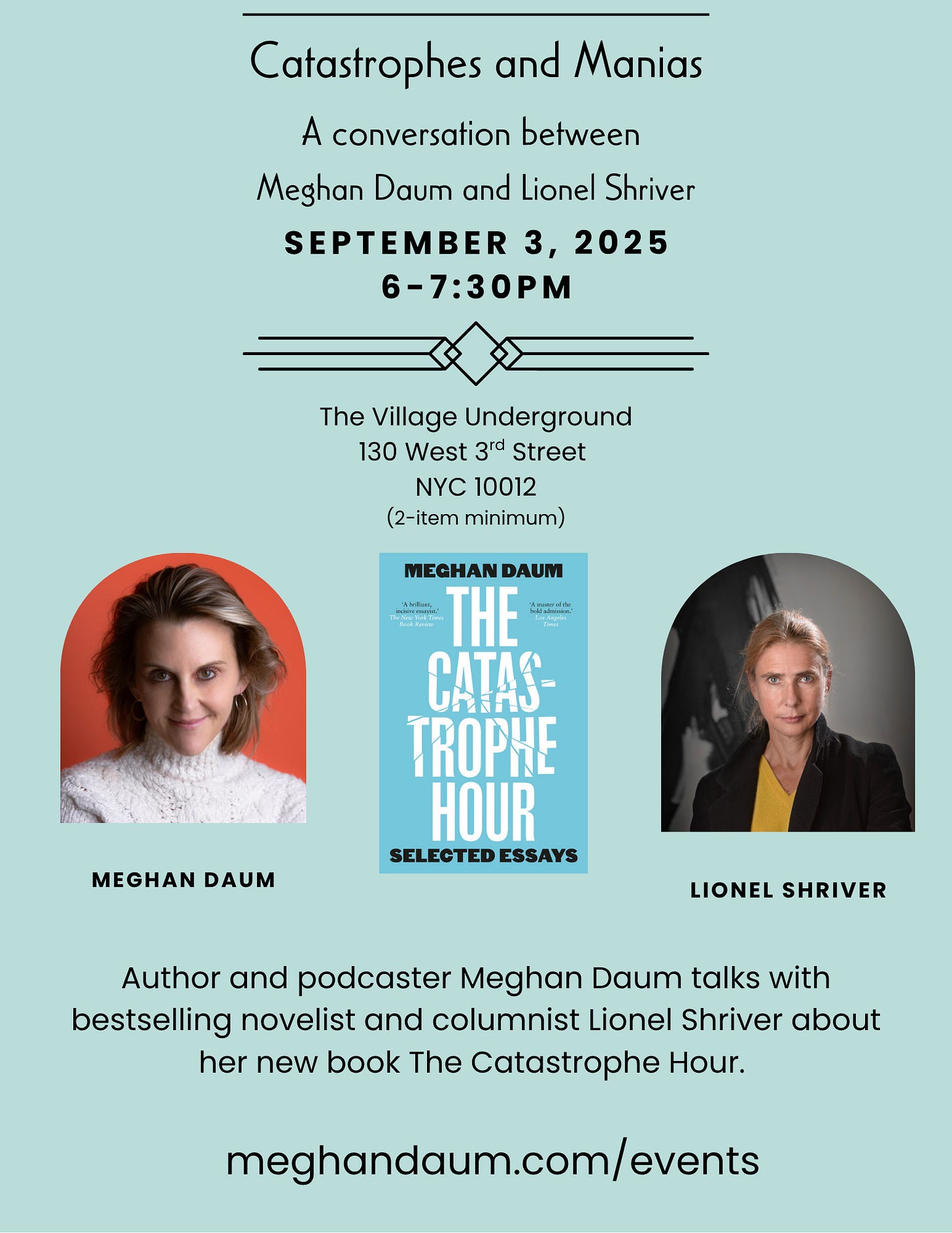

📖 Order my new book, The Catastrophe Hour: Selected Essays, on Amazon or directly from the publisher here.

🗽 Live event in NYC on Sept 3! Join me for a conversation about The Catastrophe Hour with bestselling novelist and columnist Lionel Shriver, Village Underground, 6 pm. Tickets and info here.

✈️ The Unspeakeasy’s 2025 retreat season concludes with a bigger-than-ever COED retreat with multiple speakers. October 11-12 in New York City. Programming and ticketing info here. Only a few spots left.

📺 Visit The Unspeakable on YouTube.

That concluding sentence is killer.

It's been a few years since I subscribed to The New Yorker for good reason, but it's still worthwhile to actually see how truly ridiculous it has become based on the mentality of the writers they hire...even if those Tweets were written in 2014 and 2015. Same for the old Tweets of NPR CEO Katherine Maher. All of it is worth knowing.